Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution VII (2001) history and technical infos

All good things come to an end sooner or later. So has the Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution series. This is not to say that the latest addition to the series, the Evolution VII, is a bad car but rather that it lost most part of its inherent nature. Previous models were mere excuses to get the FIA homologation in GroupA. Even so more than 150,000 Lancer Evolutions (I through to VI including the 6.5 Tommi Mäkinen edition) were sold from 1992 to 2001.

An amazing success given the awkwardness of these cars when used as everyday transport. Most examples were sold in the Asia Pacific region and very few made their way to other countries, most mainly in Europe while none was sold in North America (Emission Control Regulations again). Mitsubishi are now planning to produce more than 30000 examples of the Evolution VII!

The latest Mitsubishi representative in the World Rally Championship is now a WRC Class car rather than a GroupA Class one. The move from one class of competition car to the other frees the manufacturer’s hands from having to produce the 2500 required homologation cars that must carry the racing car’s arsenal even if it is unused/disconnected. So how does that affect the commercial version? Well the influence of the change in homologation class can be both felt and measured in the Evolution VII. For the latter one might note that performance figures are worse than they were in the previous version. Half a second is lost in 0-100km/h times (now 5.6 seconds) and a whole 1.4 seconds in the 1000m from a standing start (now 25,8 seconds). The new figures bring the Evolution VII out of the super-car territory. What has affected performance? The answer is twofold:

- A significant rise in the car’s weight, more than 50kg were added compared to the previous version

- The Mitsubishi engineers targeted more the adherence to stringent Emission Control figures and driveability than sheer performance when designing the latest engine version and its electronic management

When adding to the facts above that the car’s overall dimensions and, consequently, its inertia and aerodynamic figures have been raised one can easily realize why the Evolution VII is not the absolute point to point car anymore. It still is a very fast and capable car but when compared, side by side, to the Evolution VI and its predecessors the changes, both dynamic and static are shocking. You can access the complete car’s specification here.

The new Lancer is based on the Mitsubishi Cedia family sedan rather than on the Lancer series. This fact alone has taken away most of its aggressiveness. Some parts of its body (bonnet and front arches) are still made out of aluminum as are most of its suspension components, carried over from the previous version for their majority. This however does not manage to bring the overall weight down to more reasonable levels.

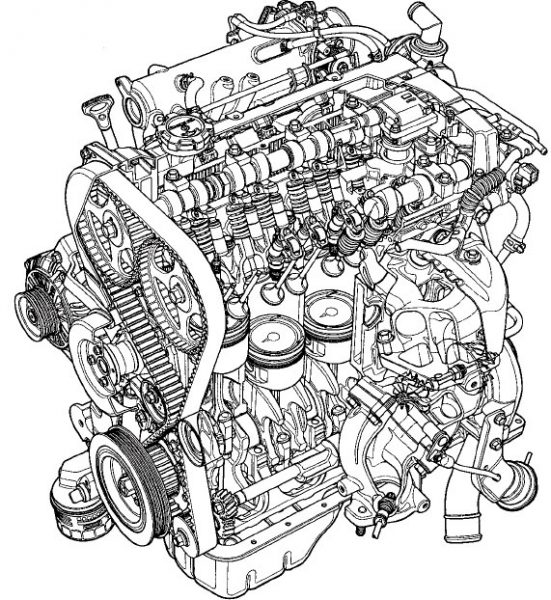

The engine is mainly the same save for the hollow camshafts and magnesium camshaft cover. The Lance Evos carry the same engine code since 1992 i.e. 4G63 whose cutout is pictured below.

The Mitsubishi 4G63 engine

The Mitsubishi 4G63 engine

These engines went through several mutations over the years but kept their architecture and extreme output unaltered. The 4G63 engine is a long stroke engine (i.e. bore is smaller than stroke) thus favoring torque over high-rev output. Mitsubishi chose to use a relatively high compression ratio, for a turbocharged engine, 8.8:1, and has therefore limited the maximum boost pressure allowed to a value lower than 1.5 bar in order to avoid detonation. The high compression ratio is an interesting and relatively innovative approach as these engines tend to be more responsive off boost than other turbocharged engines using the more classic 8:1 or lower compression ratio. In racing spec however the compression ratio used is lower than in commercial guise as in this situation off boost performance is not part of the blueprint. In competition guise the Lancer Evolution VII WRC reaches a maximum turbo pressure of 1.9 bar. Note that the turbo inlet (nozzle) area has had its diameter reduced from 105mm in previous versions to 98mm in order to favor low end response rather than high rev output. The turbo compressor wheel diameter is unchanged at 68mm.

Overall the engine’s output remains unchanged at 280bhp (the Japanese legal limit) while torque gains 1kgm and now reaches 39kgm but a whole 900rpm higher than the previous version.

Mitsubishi states that the Evolution VII chassis is 50% more rigid than that of the Evolution VI. Given the 50kg weight rise that’s the least Mitsubishi engineers could do. Chassis rigidity is the number one factor in any car’s handling abilities and the Mitsubishi numbers are more than encouraging regarding their latest creation. Previous Evo versions already displayed extremely reinforced and rigid bodies but this time the increase in the car’s size required a redesign of chassis reinforcements and the numerous new welding points were accompanied by partly seam welded steel sheets just like in full works race cars.

The new car’s transmission is were most of the changes took place. The fully equipped GSR/RS-2 version sports a TorSen front and an Active Yaw Control rear differential as previously but the center differential is now an “active” ACD differential that varies its locking characteristic according to inputs from accelerometers and other sensors. One typical “active” strategy it applies is to stiffen its locking when the car starts negotiating a corner (the braking phase) allowing for maximum deceleration, loosen the locking to negotiate the turn-in phase, stiffen a bit mid-corner allowing more torque to the rear in order to turn more easily and stiffen even more while exiting the corner to provide the maximum grip and acceleration. Well, that is the theory and it is applicable in situations such as track courses where the road surface is even and no major denivelation is present. The problem is that the Lancer is not a track car but rather a rally car. In rallying most of the racing takes place on uneven road surfaces and extremely important denivelations. How do these electronic aids cope with such terrain? Generally badly. Then why are similar systems mounted on works cars you might ask? The answer to this question is that works rally cars are equipped wiht far better and much more evolved systems costing the twice the price of the road-going version of the Lancer Evo VII and these systems are adjustable to fit the driver’s needs and the terrain requirements. Unfortunately no empirical solution can be applied and this is the main reason why the presence of such systems is more than questionable in the road-going Lancer Evo.

Note that similar locking characteristic can be achieved through purely mechanical differentials such as the TorSen or more classic disc-based Limited Slip Differentials. We here at rallycars.com are very unfriendly to whatever is electronic and is used as a commercial argument quoting abilities to “help” a car’s handling. We feel there’s nothing a car can do on its own that its driver can’t. We find that the ACD differential has set the Evolution VII to standards that undermine its character and the driver’s feel of the car. The single advantage of the ACD differential is the fact that it disconnects the rear axle when the hand brake is pulled. Further proof of the ACD differential’s counter performance is the fact that it is replaced by a classic disc-based LSD in GroupN guise.

The gearbox uses new ratios for 1st and 5th gears in the GSR/RS-2 version and super-close ratios in the RS version. The gear material has been improved and so have the gearbox bearings.

The new car’s brakes remain unchanged as their performance is satisfactory. Tire size went up a bit to 235/45×17″ but the steering ratio is still the very quick 2.2 turns from lock to lock.

Where significant progress has been achieved, compared to the previous Evo, is in the domain of suspension travel. In this field the Evo VI was suffering from too low figures, 163mm front and 160mm rear suspension travel was insufficient to avoid bottoming the suspension without using stiffer than necessary dampers. The new car has added 45mm front and rear travel to the figures above while its ride height has been lowered. The numbers apply to a GroupN , tarmac spec car. A noteworthy step forward.

Overall Mitsubishi offer a commercial package that is more civilized and politically correct than previous versions. The car’s look is far less aggressive and its everyday use rendered more realistic than ever before. Of course this new world order leads to a compromise in performance that brings the Evolution VII closer, in performance terms, to BMW and Audi cars than to its predecessors.

The competition car is, as already stated, is a WRC Class car. This class’ regulations effectively allow extensive modification of the race version that do not have to be present on the commercial vehicle. However the new car’s size is almost the biggest among all WRC cars. Only the Skoda Octavia WRC is longer and the Evolution VII has the longest wheelbase of all the contenders. That big a wheelbase, more than 2600mm, is a warrant of high speed stability but renders the car unwilling to engage in corners. Such a character can, of course, be moderated by the use of active differentials and the appropriate suspension geometry and settings but wouldn’t it have been better to start from a healthy base rather than trying to correct the inherent faults of the current one through tricks? The Evo VII was still in its early development stages in the beginning of the 2002 season so it has yet to display its real potential and we trust Mitsubishi did everything in their power to make it competitive against other cars of its class. The car was driven during the 2002 season by the very experienced François Delecour and young Alister McRae. Unfortunately Mitsubishi’s financial situation undermined the drivers and engineers efforts. After an awful and unsuccessful 2002 season the company decided to retire from the 2003 WRC in hope of developing a more competitive car.